Silent Bible Film Mystery - #04 Untangling the Pathé Passion Plays

I've been promising for a while to write a post disentangling the various Pathé Passion Plays made during the turn of the twentieth century. The films are most widely known due to the 2003 Kino-Lorber/Image Entertainment joint DVD release with From the Manger to the Cross, although obviously they are also available on YouTube. However, both the DVD and that YouTube link claim that the version of the film they have is from the period 1902-1905. Having a range of years is, in itself, a bit odd, and what's more subsequent research suggests that their dating is incorrect.

Pathé's first Jesus film was released in 1899. Gaumont produced their first Jesus film at around the same time. Over the years they evolved it and remade it such that the final version wasn't completed until 1914. By which time it's style will have been looking very mannered, though that didn't prevent subsequent re-releases. This development took two different forms. One the one hand, there was the creation of new scenes to complement the original ones. This, for example, is why a time range of 1902-05 is often ascribed to the film. The first scenes were shot in 1902 and released but new material was being filmed and gradually made available as things progressed.

On the other hand, there was also the refilming of material that had already been filmed before. Indeed, within that 15 year period there were four distinct series, one in 1899, one in 1902-05, one in 1907 with the final incarnation in 1914. For each of these material was re-shot, often improved in certain ways, such as the creation of more impressive sets - something that became a key part of the Pathé brand - larger numbers of actors, improvements in camera quality, and variations in location. At the same time there is a remarkable consistency in terms of composition and ideas, with various scenes being recreated in almost exactly the same fashion from version to version.

Three further obstacles hamper the progress of those trying to get to the bottom of this situation. Firstly, there is range of different titles given to the different editions. The films have come to be known as The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ in English or La vie et passion de notre Seigneur Jésus Christ in French, but the shorter La vie et passion de Jésus Christ or even La vie de Jésus or The Passion Play have also been used.

Secondly, there is the fact that Pathé gave distributors and exhibitors the opportunity to pick and choose which scenes they wanted to display. So a theatre owner could choose just to show the nativity scenes, or run a shorter version of the film and not have to pay for the whole thing. This is a totally different mindset to how cinema is distributed today. Given that so many copies of the film have been lost over the years it's hard to work out what is happening with various different fragments and run times of similar, but slightly different looking material.

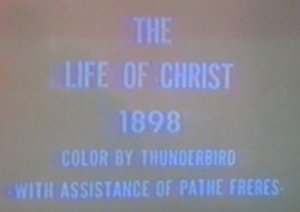

Lastly there are also various red-herrings. The film's use of colour is much discussed, but it's unclear when this first began (though it was certainly fairly early) or at what stage the colour was added to the various remaining fragments of material we have today. The film's artistic choices in terms of a central, fixed, camera became such a typical part of Pathé's house style, and Pathe's success in this era was so substantial, that it came to be seen a something primitive that later filmmakers evolved on from, rather than a creative choice. But look at a variety of 1890s and 1900s films and you'll soon see that many other approached to camera positioning and use were in evidence. And then there's the use of intertitles, which can date from far later and can themselves contain incorrect information; the release of intermediary versions; and the quality of the print which can make a newer film look far older to the uninitiated than a pristine print of an old version. A further complication is that the film continued to be chopped about, repackaged, recycled and re-released under new titles well into the sound era. I have a VHS at home which calls the film Son of Man (1915) but which comes from a release after it was "hand-colored by Nuns" in 1928.

Anyway, there's been a great deal of work into these films over the last few years, not least by Alain Boillat and Valentine Robert, Dwight Friesen, and Jo-Ann Brant, all of whom have essays in David Shepherd's book "The Silents of Jesus". Between them they break down and de-lineate the four films, which I'll summarise here with references to the relevant page in Shepherd's book:

1899

Little is known of this film. It contained 16 tableaux (p.27) and the odd scene may be included in these films I discussed back in 2006 (though I stand by very little that I wrote in that post and I think most of those are from later versions). The director is not known, but it's possible that it was Ferdinand Zecca who first joined Pathé at this time.

1902-05

This is the version that the Image/Kino DVD claims to be, but it appears they are mistaken. We can forgive them - it they had not painstakingly restored this film and made it widely available, the subsequent research which has cleared things up a little might not have happened. There was a VHS release in 1996 by Hollywood’s Attic (31). In any case, it was directed by Ferdinad Zecca and his assistant / co-creator Lucien Nonguet. As the time range suggests this was the most evolutionary stage. The 16 original tableaux were reshot - some longer some shorter - and new titles were added (p.27). Then over the following three years additional tableau were created, taking the eventual total to 32 (p.27).

1907

This is the version that is available on the Image/Kino DVD, or at least that is one of them because two very, very slightly different versions exist, one in black and white and one in colour, though the differences extend to marginal variations in composition, not just the use of colour (p.79f). The number of tableaux in this version are hard to number with precision. Boillat and Robert state 37; Friesen cites 39 (p.79), but only lists 35. In many ways Zecca seems to be responding to his friend and rival Alice Guy's 1906 Jesus film (p.87-92) as evidenced by the increased percentage of outdoor footage at a time Pathé was increasingly building its reputation on its sets (as evidenced by the now prominent Pathe logo on several of them). The film has been discussed in many places at length, so I'll say no more on this for now.

1913-4

In contrast to the previous two or three stages, the fourth and final film was directed by Maurice-André Maître. It's this version which was re-released as Son of Man in 1915 and again after 1928 and for several years was available on VHS from Nostalgia Family Video. As you might expect everything here is bigger and better. Abel claims that there were 75 tableaux, but Boillat and Robert, writing more recently reduces this figure to 43 (p.27). Brant notes how his use of "deep staging and misè en scene "intensify the pathos", "dramatize the logic", provide a "more complicated visual experience" and "liberate his story" (158). Again he uses more outside scenes, bigger crowds and scenery, but he uses this to increase his depth of field.

I hope this helps clear up some of the confusion over the various films - I must admit it's still not entirely clear to me, and still I watch the DVD I discussed back in 2006 and long to know the story of how what seems to be a jumble of fragments came to be assembled in this way. In writing this post I also sat down and watched the two later films together in parallel, pausing one or the other to keep the episodes in sync. That in itself was enough of an interesting exercise to make this worthwhile.

1 - Abel, Richard (1994) The Cine Goes to Town: French Cinema 1896-1914, Berkeley: University of California Press. p.320

Labels: French Bible Films, Life and Passion of Jesus Christ, Pathé, Silent Bible Film Mysteries, Silent Jesus Films