Silent Bible Film Mystery - #05 Christus (1914/1916)

Back in 2007 and 2008 I wrote a couple of posts about the Italian Jesus film Christus. At the time there was a bit of a problem with what the date of the film was (was it 1914 or 1916?). As part of my research on Italian Jesus films I've been looking back at this film again, and it turns out that there were two different films called Christus one released in 1914, the other in 1916 or maybe even 1917.

I guess it's time for another instalment of Silent Bible Film Mysteries.

Firstly there is some confusion as to who directed which film. The cover of the DVD I have, cites Giuseppe De Liguoro as the director, but the film itself does not name the drector. Other sources cite Giulio Antamoro, with others mentioning Enrico Guazzoni's Quo Vadis? (1913). The film is on YouTube several times but usually attributed to Antamoro.

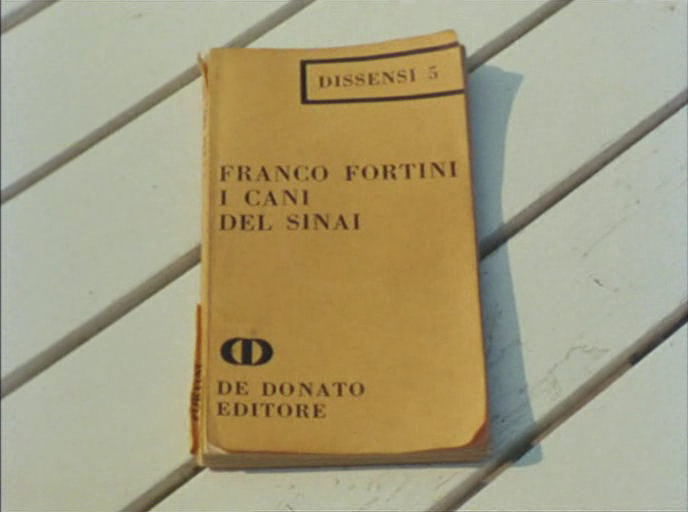

It turns out that this mystery isn't quite as mysterious as some of the others in this series. Discussion about a film called Christus is mentioned in a number of sources (Bertellini's "Italian Silent Cinema", Shepherd's "Silents of Jesus", Campbell & Pitts' "The Bible on Film", Kinnard & Davis' "Divine Images" and Adele Reinhartz's "Jesus of Hollywood", all of whom identify Antamoro as the director.

Pucci (in Shepherd) names De Liguoro as the director of a different film called Christus (200) and even notes the confusion caused by this Grapevine release, which is different from the one I bought from them over a decade ago (207). Both he and Bertellini (134n38) give the alternative title of De Liguoro's film. La sfinga della Ionio (The Sphinx of the Ionian Sea).

A little googling brought up a bit more information about the De Liguoro film (pictured above). Whilst Rome was fast becoming the film-production capital of Italy, the industry was growing in other regions as well. De Liguoro’s 1914 Christus had been filmed and financed in Sicily. Filmmaking did not start on the Catania side of the Island until 1914 so Liguoro’s film, based on a local legend about a sphinx-shaped outcrop of rocks, was amongst the first shot in the region. It was made under the banner of Etna films, funded by local industrialist Alfredo Alonzo, which targeted their output at the local, upper class market whilst seeking to engage a broader audience (Bertellini, 130).

The Christus of the title, however, is not Jesus Christ, as you might expect, but the name of a character from an entirely different story set around 1000 B.C. In 2014 an Italian paper ran a series looking back at their community a hundred years previously. You can read the original article in Italian, (or have a look at this translation to English), which includes the following summary:

"Christus tells the story of the impossible love of the lustful, corrupt, governor of Syracuse Xenia, for the young Christus, in love with the sweet Myriam, with punctual and atrocious death in the flames of a galley (built ad hoc) of the cruel Xenia, while Christus, together with old Gisio, manages to save Miriam locked up in a well. Meanwhile the protagonist, together with old Gisio, succeeds in saving Miriam who had been locked up in a well"The article also makes it clear that Alonzo, inspired by Cabiria (1914) earlier in the year pumped a vast amount of money into Etna films, and that this epic was their most costly and spectacular production. In addition to a reputed cost of 300 extras and several major stars there was also the creation of vast sets and a ship for the scenes at sea. Sadly though it seems the film's marketing efforts failed to get any traction, with even the local media underplaying it, and it never broke out to become the European/Worldwide smash that Alonzo/Etna needed to recoup costs.

The confusion in this case however seems to be limited to Grapevine video and customers like me. Aside from their case and the surrounding confusion there is nothing else linking De Liguoro with a Jesus film called Christus. Whilst Grapevine no longer seem to sell the DVD set I bought they continue to market a film they claim is De Liguoro's Christus, but according to Pucci's endnote the film supplied is Maître's 1914 Life and Passion of Jesus Christ the subject of Silent Bible Film Mystery #04 (207n1).

In summary, then, we have two films. The 1914 Christus, also known as La sfinga della Ionio (The Sphinx of the Ionian Sea),was made in Sicily by Etna films with Giuseppe De Liguoro at the helm. Rather than being a Jesus film however, it's a story from 100 years previously, whose hero (played by Alessandro Rocca) is simply called Christus, though it's biggest star was Alfonso Cassini in the role of Gisio.

Then there is the Jesus film called Christus released two or three years later in 1916/1917 was directed by Giulio Antamoro for the great Cines firm. This is the film I wrote about and which has been covered by the other authors listed above. a version of this film, (labelled correctly) is also available from Grapevine, though the print of the film on YouTube is better if you can hack the fairly occasional subtitles being in Italian. Jesus is played by Alberto Pasquali, and it's worth looking at CineKolossal's page on this film, for the sheer number of screenshots and stills (though they date it 1914 which is seemingly date production began). And it turns out that whilst Antamoro filmed most of the picture, Guazzoni did direct a few shots including part of the ascension scene (Pucci 201).

========

Bertellini, Giorgio (2013) “Southern (and Southernist) Italian Cinema” in Bertellini, Giorgio (ed.) (2013). Italian Silent Cinema: A Reader (New Barnett: John Libbey Publishing), pp. 123-134

Pucci, Giuseppe (2016) "Christus (Cines, 1916): Italy's First Religious 'Kolossal' by Antamoro and Salvatori" in The Silents of Jesus in the Cinema (1897-1927); ed. Shepherd, David. pp.200-210

Labels: Christus, Italian Bible Films, Silent Bible Film Mysteries