Flicker Alley / Lobster's Bluray release: The King of Kings (1927/28)

I was provided with a copy of this set for the purposes of reviewing it.

More than 20 years after its Criterion DVD release, Cecil B. DeMille's monumental biblical epic The King of Kings (1927) has finally received an English language Blu-ray release courtesy of Flicker Alley and Blackhawk films. It's a lush two-disc set which comes with two different cuts of the freshly-restored film, a 28-page booklet and a host of extras.

The film

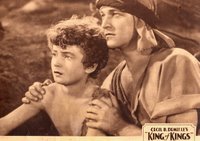

While DeMille is mainly remembered these days for his historical epics, only one of the fifty films he had made before taking on The King of Kings had been biblical (The Ten Commandments, 1923): he was known mainly for westerns and melodramas. Nevertheless The King of Kings is one of the silent era's crowning achievements, as the Jesus story is told in the midst of huge back drops, impressive costumes and, of the obligatory cast of thousands. If the portrayal of Jesus is a little paternalistic and some of the soft-focus lighting seems a little twee by today's standards, H.B. Warner's portrayal of Jesus was fairly ground-breaking in its day for its tougher, more human portrayal of the man from Nazareth.

Starting in the middle of Jesus' ministry, the film sets out its stall from the off. A glamorous courtesan, Mary Magdalene reclines in her opulent villa surrounded by a glut of rich and powerful admirers. When she enquires about her lover, one Judas Iscariot, she is infuriated to hear that he has transferred his attentions to a simple carpenter. Thus DeMille sets out his stall from the very beginning, laying out what would become his trademark style: a mix of sex and piety that gave audiences what they wanted and then lectured them lest they enjoyed it too much. Mary's more flamboyant side is soon subsumed under a black cloak, her coiled, gold bra never to return again.

Meanwhile Jesus shores up support from those both outside Jerusalem and within with miracles, wise words and occasionally saving a slut-shamed women, all of which infuriate the Jewish high priest, Caiaphas. When persuades Judas to betray him, Jesus' fate appears sealed.

At the time it was made, the film was the most expensive film Hollywood had made, and despite never receiving a version with spoken dialogue, it remained popular with audiences long into the sound era.

The discs

There are two Blu-ray discs both of which feature newly restored versions of the film and are multi-region encoded (i.e. region free). The contents are as follows:

Disc 1

1927 Roadshow version of the film (161 mins*; 1.33:1 ratio) with an audio commentary by film historian Marc Wanamaker. New orchestral score updating and extending Hugo Riesenfeld's 1928 score, composed and updated by Robert Israel and available in both stereo and 5.1 Surround Sound.

Disc 2

1928 general release reconstruction (115 mins*, 1.33:1 ratio)

Two Scores for the 1928 General Release - Hugo Riesenfeld's original orchestral score and an organ score by Christian Elliott.

Substantial range of extra features.

I'll discuss the extra features in a little more detail below, but first some comparison of these two versions of The King of Kings is in order.

The cuts

There now a few versions of this film available on DVD (not to mention various editions on YouTube and other streaming sites) largely due to the fact that at the time several different versions of the film were released. The longest cut was the "Roadshow version" which is the one shown at the film's premier in New York in 1927. But the film received complaints from various Jewish groups who were concerned it blamed the Jews for the crucifixion and were unhappy with the portrayal of the high priest Caiaphas. So, early in 1928, DeMille recut the film to take their views into consideration.

But things were moving quickly on another front, with the advent of the sound era. An even shorter third cut of the film was made for general release, and while the dialogue remained silent, a variety of sound effects were added, such as the howling winds that accompanied the moments following Jesus' death.

It was this shorter 'General Release' version (around 115 minutes) that was released on VHS in 1997 and has been released several times since, including a UK version in 2006 by Home Entertainment.

However, in 2004, Criterion released a 2-disc set including both this shorter 1928 cut of the film and the original Roadshow version (they gave the running lengths as 112 minutes and 155 minutes respectively). The Criterion discs also featured coloured footage for the resurrection scene (both discs) and the opening scene for the Roadshow version.

Flicker Alley's new release offers two versions of the film both on Blu-ray. While these broadly correspond to the two versions in the Criterion edition, there are substantial differences. So I thought it would be useful to highlight the differences between Flicker Alley's edition of the longer Roadshow version with the Criterion edition and also to discuss the differences between the two Flicker Alley discs themselves.

1927 Roadshow: Flicker-Alley Blu-ray vs 1927 Criterion DVD

Clearly the biggest difference between the two editions here is that Flicker Alley's restoration is on Blu-ray and, as you'd expect, the HD delivers a substantial improvement.

However, there are also key differences with the colouring of the film. While the Criterion disc was the first to offer both the resurrection scene and the opening scenes in its original Technicolor, the rest of the presentation is in black and white. However, we know from fragments of the original reels that the other scenes were colour-toned. It was only when the synchronised sound track was introduced that the toned footage was changed to black and white.

The Technicolor scenes are a remarkable improvement on those in the Criterion edition. Criterion's images looked too green, whereas Flicker Alley have used the original technique of adding a yellow tint into the mix. This combined with another alterations results colours that are both more natural and more vibrant. The red dress worn by Jesus' mother during the resurrection is particularly striking.

The comparison between the toned sections and Criterion's plain black and white will be more down to personal preference.. At first sepia is used, with the occasional hint of orange and this runs until the Garden of Gethsemane/night before Jesus' death, which uses blue as was customary for night-time scenes. There's a return to sepia for the trial scenes before switching to yellow for the crucifixion scenes. The final scene – after the Technicolor resurrection – reverts back to sepia.

Personally I adore the blue, but I'm unconvinced by the yellow crucifixion, which might be my least favourite aspect of the set as a whole. It is authentic, though, so that's between Mr DeMille and me. As to the sepia sections, my preference for them over the black and white is on a more shot by shot basis so it's nice for completists to have both available.

Strikingly, the new edition also contains a third type of colour, hand-painted colour. This was something DeMille originally commissioned Gustav Brock to do in the scenes featuring soldiers in the blue-toned sequence. The flames of their torches were hand-coloured. It was something that had to be done on each individual print and so we have no idea how many prints were altered like this, aside from that which was shown at the premieré. Almost as painstaking was the modern process which has re-added this colour into these scenes. The results are pretty spectacular. This is partly because of the contrast between the calming blue that otherwise fills the screen and the small intense bursts of flame dotted across the canvas. But it's also partly because the unnaturalness of these colours gives them an expressionistic edge.

Those who love scanning the details of different releases may have noticed that whereas the Criterion edition claims to be 155 minutes, the length of the new edition is given as 161 minutes. Alas, this does not really signify the addition of new material in the Flicker Alley release. For one thing, Criterion understated the length of their edition which actually comes in at 157m26s. In contrast, Flicker Alley rounded up their 160m56s run-time (quite understandably).

The remaining 3m30s is largely due to a bit more information in the opening titles before the film starts and the addition of modern-style credits sequence at the end. Some sequences run a tiny bit slower in the Flicker Alley cut (see below). The only new material, therefore, is the inclusion of an "Intermission" intertitle, followed by one announcing "The King of Kings II".

Flicker Alley's Blu-rays: 1927 Roadshow version vs 1928 General Release version

There are substantial differences between the two version of the film in this collection. The most obvious one is the 46 minute difference in running time. The first reason for this is that the 1927 Roadshow version includes a number of additional scenes which were completely cut in the version released the following year. The most notable scenes omitted are Judas failing to heal a boy with a demon, the call of Matthew, and the miracle of Peter finding a fish with a coin in its mouth.

However, the abridged version from 1928 also shortens may of those scenes it does retain. There are extra shots of leopards here, Caiaphas fondling Roman coins there, with the later being one of the more obvious cuts made to exorcise the film of antisemitic content. The longer scenes give a broader sense of Jesus' life outside of Jerusalem and of characters such as Mary the mother of Jesus, who co-witnesses the resurrection in the longer version, but is pretty much reduced to an early walk-on role in the later version. But it's also noticeable that the order of these scenes, or shots within the scenes, is different too. The woman accused of adultery is introduced much earlier into the story, for example.

Other differences are more visual. Perhaps the most significant difference is that – apart from the resurrection scene – the General Release version is all in black and white. It uses different intertitles in places and occasionally puts them in a different part of a sequence. The cropping and screen ratio is the same, however (even though the silent Roadshow version would have had a taller frame than the General Release version, due the space required on the frame for the synchronised soundtrack).

The commentary

Having recorded a solo commentary track for a Jesus film, I'm all too aware of the challenge of coming up with sufficient material to maintain interest for two-plus hours. Wanamaker is certainly up to the task, providing commentary from a variety of perspectives. He produces all kinds of fascinating details about the making of this epic production such as DeMille choosing to shoot a scene on the Mount of Olives in an olive grove in his neighbourhood; him keeping the great gates from Pilate's villas for his own house, or the use of a hidden bicycle seat for H.B. Warner to perch on while shooting the crucifixion.

While it's at it's best when Wanamaker is giving the details around the production, at other times the commentary falls back onto simply describing the basics of the plot, or the primary action on screen. Occasionally it offers some more theologically inclined reflection, but it's at a fairly elementary level. Moreover, there is perhaps a little too much willingness to accept at face value DeMille's claims about the depths of his team's research. These parts can be very interesting, but they are not necessarily an accurate reflection of what scholars know about the history of the actual events and their context, partly because so much more has been uncovered since the film was made. Nevertheless Wanamaker's insights as Film Historian prove useful throughout.

The extra features

The extra features are great in this set, not least because Lobster Films' Serge Bromberg voices several of the more technical ones.

Top billing goes to "The Making of The King of Kings" which provides 21 minutes of footage behind the scenes of the film. There's an optional commentary on these candid shots, provided again by Marc Wanamaker.

"The King of Kings Set Visit" is fairly similar to the above, but features various members of the film industry touring the set during production. These are primarily producers rather than stars, so this material is a little more stiff. Similarly "Footage from the film's premiere in Germany" is interesting if you like people watching – and there are some real moments where you feel like you connect with ordinary faces from the past –but this won't be to everyone's taste.

In quite a different vein is "Pathé Week on Broadway". This is a promotional animated short from 1927 that officially announces the release of the film, as well as several others being distributed by the recently formed Pathé-DeMille company. Shot in the style of Paul Terry, whose studio had recently joined Pathé-DeMille, the intention seems to have been to promote not just The King of Kings but also their other films, that were all showing on Broadway in a single week. It has moments of both intentional and unintentional humour: the latter exemplified by a group of cartoon chickens starring at a poster for what feels like minutes, a poster which just happens to be announcing all the locations where these films would be appearing. It's fascinating as an insight into the period and the unconventional ways that filmmakers sought to get attention, not least because it's difficult to imagine Mel Gibson using a brood of hand-drawn poultry to promote his sequel to The Passion of the Christ.

"Negative A / Negative B" is the first of the three Bromberg featurettes which tackle more technical matters surrounding the original film, practices at the time, and the restoration process that he has overseen. This first mini-documentary explores the filming process that led to multiple negatives, namely the use of multiple similarly located cameras, simultaneously filming the same action from three different locations. It includes a little of the behind-the-scenes footage from "The Making of The King of Kings" featurette which shows three cameraman in tandem, hand-cranking their cameras. This also seems to explain why different versions of the film seem to go faster and slower relatively to each other when watched side by side.

Naturally, given the film's pioneering use of Technicolor, the extras includes an exploration of the process that produced the movie's colour scenes. "Technicolor" is short but incredibly insightful, though I feel I may need to rewatch it to grasp it all fully. Bromberg again provides the voiceover.

Finally "Hand Coloring onto the Film" which looks at those scenes of the soldiers arresting Jesus and the process of colourising their flames individually. It's quite an insight into both the historical process of hand-colouring as well as the methodology and philosophy around restoring these scenes to how they would once have looked.

The set also features three photo galleries. The largest of these holds almost a hundred production stills, everything from the building of the set to photographs of mass being celebrated on location. Then there is what is called a "portrait gallery" featuring 26 images, although these are better described as promotional stills. Many of these are of single characters (including most of the disciples) posing in costume against plain backgrounds, though curiously Peter and Jesus are not included. Thirdly, there are 49 images of the film playing in various theatres.

The final extra feature is the full text of a Variety article announcing the changes DeMille was making due to the concerns of the Jewish Anti-Defamation League. It's interesting just how willing DeMille appears to have been to accommodate the ADL's feedback, to the extent that they were fully satisfied he had met their demands. The ADL's concerns were particularly driven by how the film might be received in other territories and it's striking to see these sentiments expressed so close to footage of the film opening apparently unhindered in inter-war Germany just as Hitler was coming to prominence.

The booklet

A 28-page booklet comes with the set and features: an introduction by Bromberg; a little more detail about the three different cuts of the film; an article DeMille wrote for the June 1927 issue of Theatre titled "The Screen as a Religious Teacher"; some details about the restoration of the film; and "Some Notes on Robert Israel's Score". These nicely complement the extra features on disc two, and include a few further images.

The set also comes with a reversible Blu-ray case sleeve giving two artwork options. The first features a newly designed cover based on a sketch of H.B. Warner's Jesus by fellow actor H. Montagu Love. Love played a centurion in the movie and starred in numerous epics during his 173-movie career. The other option is with the same monochrome silhouette as the Criterion DVD release. In my opinion, it would've been nice to have at least one option that used an image from the film itself, but perhaps I'm in the minority on that.

The verdict

Flicker Alley's Blu-ray release of DeMille's The King of Kings (1927 & 1928) is most welcome. It's great to have this important film not only transferred to HD format but also to have received the attention and care it deserves. The effort taken with the longer original Roadshow version (1927) to not only restore existing prints, but also to ensure the film was returned to how it was originally intended to be seen, is considerable and much appreciated, as is the new 5.1 Surround Sound score. Likewise it's good to have the shorter General Release version from 1928 available on Blu-ray as well especially with a choice of scores.

On top of these two restorations, Flicker Alley have also assembled a great and varied selection of extra features, a good commentary and an interesting booklet, meaning that the vast majority will not only learn about this film, but also about the silent era in general.

Labels: DeMille, DVD News, King of Kings (The - 1927), Silent Jesus Films