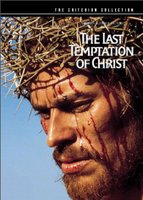

Both the written and the cinematic version of Nikos Kazantzakis's Last Temptation of Christ caused controversy on their release, and (as I noted in my recent podcast on the film), it's still difficult to discuss either project today without getting bogged down in the strident objections that have been levelled at both works.

Both the written and the cinematic version of Nikos Kazantzakis's Last Temptation of Christ caused controversy on their release, and (as I noted in my recent podcast on the film), it's still difficult to discuss either project today without getting bogged down in the strident objections that have been levelled at both works.So news that Darren J. N. Middleton was pulling together a series of essays to celebrate the fiftieth anniversary of the books publication, was most welcome, particularly as it promised to offer a "balanced, critical assessment of Kazantzakis's novel and Scorsese's subsequent film". Indeed it's clear that in "Scandalizing Jesus? Kazantzakis's The Last Temptation of Christ Fifty Years On", Middleton has done exactly that. His chapter "Satan and the Curious: Texas Evangelicals Read the Last Temptation of Christ", opens the second part of the book, and it is the only one which is primarily concerned with the outrage that has been caused by this story. It doesn't really bring much that is new to the table, but its balance and measured examination is certainly a breath of cool fresh air into an often heated debate.

Similarly, Middleton deserves credit for inviting one or two of the writers who very evidently disapprove of the works, For example, Lloyd Baugh's chapter "Martin Scorsese's The Last Temptation of Christ:A Critical Re-assessment of Its Sources, Its Theological Problems, and Its impact on the Public" is effectively a re-working of his chapter on the film in his "Imaging the Divine". Thankfully, they respond in kind: their comments are measured and fair.

As would be expected, the first section of the book is the longer, featuring 11 essays on Kazantzakis's "Literary Lord". After a strong start by Last Temptation translator Peter Bien, Jesus film critic W. Barnes Tatum, and Kazantzakis expert Lewis Owens, the first section seems to lose it's way a little. Bien examines the impact of Renan's "Vie de Jésus" on Kazantzakis and Tatum picks up the thread looking at how the novel relates to the quest for the historical Jesus. His chapter is clearly laid out, succinctly concluded, and puts its point across very well.

As would be expected, the first section of the book is the longer, featuring 11 essays on Kazantzakis's "Literary Lord". After a strong start by Last Temptation translator Peter Bien, Jesus film critic W. Barnes Tatum, and Kazantzakis expert Lewis Owens, the first section seems to lose it's way a little. Bien examines the impact of Renan's "Vie de Jésus" on Kazantzakis and Tatum picks up the thread looking at how the novel relates to the quest for the historical Jesus. His chapter is clearly laid out, succinctly concluded, and puts its point across very well.In comparison the three chapters which follow Owens's are a chore to read. Lifelessly written and full of technical jargon they seem to take no account of the variety of backgrounds their readers will have. Essentially this book will find readers from across four disciplines: theology, philosophy literature and film studies. To repeatedly introduce philosophical terms, and leave them undefined for readers unfamiliar with philiosophy, say, is at best thoughtless.

It's difficult to decide where exactly the fault lies for this. Whilst some blame obviously lies with the authors, we obviously don't know what their brief was. Were they aware of the inter-disciplinary nature of the book? Even so, perhaps some blame rests with the editor. Middleton, at least, should have been aware at how impregnable some of these chapters are to outsiders, and suggest areas where greater clarity could have been brought.

Of course, it's possible that I'm just trying to excuse my own ignorance. And certainly, some ideas and concepts are far harder to communicate than others. Nevertheless, I can't help but wonder how often legitimate criticisms are held back for fear of looking stupid. If, in a work of numerous authors, some chapters are lucid and eloquent, whilst others are confusing and impregnable, might this at least suggest that part of the fault lies with the authors of those weaker chapters?

Fortunately, just when I was on the verge of abandoning the literature section entirely, and just sticking to the "Screen Savior" part of the book, Roderick Beaton's chapter gave me fresh hope. "The Temptation that Never Was: Kazantzakis and Borges" notes similarities between "Last Temptation" and the work of Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges and philosopher Henri Bergson. Beaton makes the novel suggestion that Jesus's last temptation is simply Kazantzakis allowing Jesus to have "had it both ways".1 It's one of the books most interesting essays although Beaton relies on ignoring Kazantzakis's prologue, which is somewhat problematic. Interestingly the film presents the "temptation" sequence in such a way as to rule out Beaton's oppositional reading.

The rest of the first section continues without ever reaching the highs or lows of the chapters that have preceded it. Jen Harrison's examination of "Women in Pre-Easter Patriarchy" voices the long overdue observation that the "there is only one woman in the world"2 quotation actually comes from the mouth of Satan during the temptation sequence. She argues, therefore, that it should not be taken as an example of misogyny within the minds of either Kazantzakis or his leading man.

The second "half" of the book consists of only 6 chapters including Middleton's and Baugh's as discussed above. The last of these is by Martin Scorsese, and whilst it's a most welcome addition to this volume, at just over a side in length, it's little more than a footnote. Certainly anyone who bought the book because Scorsese's name appeared on the cover will be disappointed – they would be better off with the relevant portion of "Scorsese on Scorsese".

The second "half" of the book consists of only 6 chapters including Middleton's and Baugh's as discussed above. The last of these is by Martin Scorsese, and whilst it's a most welcome addition to this volume, at just over a side in length, it's little more than a footnote. Certainly anyone who bought the book because Scorsese's name appeared on the cover will be disappointed – they would be better off with the relevant portion of "Scorsese on Scorsese".The remaining three chapters are by Melody D. Knowles and Alison Whitney, Randolph Jordan and Peter T. Chattaway. Peter is a good friend of mine, so I find myself unable to offer an objective position on his chapter. Nevertheless, it seems, to me at least, that it's one of the book's best entries. He looks at "Sexuality and Christ" in four different locations: Christian theology, art and film, Kazantzakis's novel, and Scorsese's Film with some great insights into each.

The other two chapters revert to the hit and miss pattern that is typical of the book as a whole. There's nothing wrong with Randolph Jordan's essay, but it feels slightly out of place here. It's not so much an essay about this particular film as one about the relationship between sound and film in general, which happens to use Last Temptation of Christ as a pertinent example. Jordan's observations are articulately expressed, and contain some interesting insights, but they would be best served in another volume - perhaps one examining the relationship between sound and image in cinema.

By contrast, Knowles and Whitney's chapter really hits the mark. Drawing on their experiences of discussing the film with seminarians they bring to the table a wide range of perspectives on the film – many of which could easily spawn essays themselves. This is one of the chapters of this book I can imagine myself returning to time and time again.

In addition to the book's two main sections it is topped and tailed by Don Cuppitt's Foreword and Austin S. Lingerfelt's Webliography as well as a further reading section. Like Scorsese's chapter, Cuppitt's introduction barely stretches over a side. The Webliography and further reading sections are far more extensive and offer a great range of writing on both the book and the film. One minor criticism here, however, is that the date of access for most of the web resources is in late 2003. Since the book was not published until November 2005, it was almost two years between the last date of access and the book's publication. Things change so swiftly in cyberspace that this seems an awfully long time. I don't imagine for a minute that this is Lingerfelt's fault – far more likely to be the fault of the publishers – but it does raise the question of how worthwhile such an exercise was if it was to be handled this way.

It perhaps sums up the book as a whole - a great idea, with some fascinating insights, but several disappointments along the way (strangely, this is also how I feel about Scorsese's film). In particular, too many chapters are either a little tangential, poorly communicated or unnecessarily verbose. Whilst fans of either the book or the film will no doubt appreciate the numerous new ways to look at these two works, they may well wonder at the end if it was worth all the effort.

=======

1 - Beaton, Roderick. "The Temptation that Never Was: Kazantzakis and Borges" in "Scandalizing Jesus? Kazantzakis's The Last Temptation of Christ Fifty Years On" p.90

2 – Kazantzakis, Nikos. "Last Temptation of Christ" (1960), p.66

This comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDelete